Is Manufacturing-Led Export still the Golden Path

for Developing Economies?

Introduction

For decades, manufacturing for export has long been a foundation of successful economic development—especially in East Asia, where countries like South Korea and Singapore transformed their economies by producing goods for global markets. This strategy, known as manufacturing-led export, not only fuelled rapid industrialization but also helped create jobs, earn valuable foreign exchange, and integrate these nations into the global economy.

Today, however, the global landscape is shifting. Automation, artificial intelligence, rising protectionism, and intensifying international competition are challenging the long-standing viability of this approach. In response, new development strategies have emerged, prompting many economies to reconsider their future pathways.

In this context, the blog provides a comprehensive overview of the manufacturing led-export strategy, exploring its benefits, its historical success, current challenges, and the alternative development models gaining interest. It also raises a critical question: How essential is this strategy for today’s developing countries, and how can premature deindustrialization be avoided?

Furthermore, the blog highlights Egypt’s industrialization position over the years, and how it can navigate through today’s global economic shifts while benefiting from manufacturing to its full potential.

Manufacturing-Led Export Strategies and the Shift Toward Services [i] [ii]

Manufacturing-led export is an economic development strategy in which countries prioritize the production of goods specifically for international markets rather than domestic consumption. This approach emerged in the mid-to-late 20th century and was most successfully adopted by East Asian economies such as China, South Korea, and Singapore, which achieved rapid industrialization and export growth by initially relying on abundant unskilled labor before gradually upgrading toward more sophisticated manufacturing activities.

East Asia’s success was not driven by manufacturing alone, but by a coherent development model that combined industrial expansion with strong investments in human capital and effective economic governance. Governments invested heavily in basic education, health and nutrition, and family planning, not only to meet social needs but also to raise labor productivity. At the same time, policymakers maintained macroeconomic stability and fiscal discipline, while using targeted industrial policies—such as import controls and preferential credit—to support exporters and strengthen domestic industries [iii].

This model generated several well-documented benefits. Access to global markets enabled countries to earn foreign currency and strengthen their external balances. Manufacturing activity created important spillover effects, improving education systems, financial institutions, and productivity across other sectors. Export-oriented industries also contributed to higher tax revenues, as formal manufacturing activities were easier to regulate and tax than informal economic activities. Moreover, job creation and urban growth accelerated as manufacturing absorbed labor transitioning out of

agriculture, gradually increased wages, and stimulated demand for local services, reinforcing broader economic development.

Despite these clear benefits, the manufacturing-led export strategy now faces significant drawbacks and structural challenges, particularly in today’s global economic environment. Intense global competition, especially from China, has made access to international markets increasingly difficult for latecomer economies. In many developing countries, weak industrial policies have failed to adequately support and upgrade domestic manufacturing capabilities. While unskilled labor once represented a strong comparative advantage, limited human capital has become a major constraint, as modern manufacturing increasingly requires higher skill levels. In addition, automation and artificial intelligence are reducing labor demand in factories, undermining one of the traditional strengths of manufacturing in developing countries—its capacity to absorb large numbers of low-skilled workers. These challenges are further compounded by rising protectionism, as countries impose trade barriers to protect domestic industries from foreign competition[i].

As a result of these drawbacks, alternative development strategies have emerged, offering new pathways for growth and employment. One such approach is the skill-intensive services strategy[ii] [iii], which focuses on expanding high-skill, knowledge-based sectors such as information technology, finance, consulting, and research services. These sectors are globally tradable and can benefit from international demand. However, this strategy often struggles to be inclusive in low-income countries, where only a small share of the workforce possesses the required education and expertise. For example, in India, less than 2.5% of workers are employed in skill-intensive services.

Another approach is the non-tradable services strategy[iv] [v], which emphasizes the expansion of domestic service sectors such as retail, construction, tourism, and hospitality. These sectors can absorb large numbers of workers and support more inclusive growth, particularly in low-income economies. Nevertheless, they are often characterized by low productivity, increasing exposure to automation risks, and limited potential to generate the long-term structural transformation historically associated with manufacturing.

The growing adoption of these alternative strategies—often at the expense of manufacturing—has contributed to premature deindustrialization in developing countries, where economies shift away from manufacturing before the sector reaches its full potential in terms of productivity growth and employment absorption. While no single development strategy is universally superior, and each country must tailor its approach to its own resources, institutional capacity, and policy environment, evidence suggests that for low-income countries, alternatives to manufacturing-led export have been less effective in delivering sustained productivity gains and broad-based employment[vi].

How Manufacturing Evolves with Development: The Risk of Premature Deindustrialization

Although services can and should play a role in economic development, they do not fully substitute for the transformative role of manufacturing. Early and unsequenced shifts toward services—often driven by mounting challenges in manufacturing—risk weakening the industrial base and limiting long-term growth prospects. These dynamics highlight the critical importance of timing and sequencing in the development process.

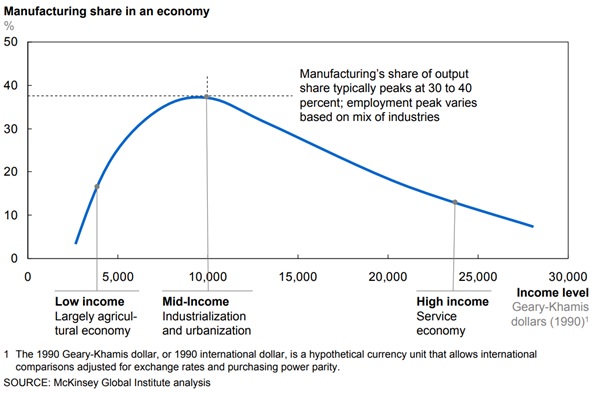

As economies develop, the contribution of manufacturing generally follows an inverted U-shaped pattern. In the early stages of development, manufacturing’s share of GDP rises rapidly as countries transition from agriculture to industry. During this phase, manufacturing acts as the primary engine of growth—creating jobs, expanding exports, and generating significant productivity gains. This is the stage at which industrialization delivers its strongest developmental impact.

As represented in figure (1), as income levels increase, economies enter a middle-income phase in which manufacturing’s share of GDP stabilizes and often peaks, typically reaching around 30–40% of GDP. At this point, countries begin to diversify into services and higher-technology activities. This stage represents a critical turning point: economies that successfully upgrade their manufacturing base—by moving into more complex, higher-value production—are able to sustain growth and continue their development trajectory. Those that fail to do so risk stagnation and getting stuck at the middle-income level.

In the later stages of development, manufacturing’s share of GDP gradually declines—though not necessarily in absolute terms—while the services sector expands rapidly. Several structural factors explain this shift. Prices of manufactured goods, particularly durable goods, tend to rise more slowly than overall inflation because technological innovation continuously improves production efficiency. In addition, many activities that were once counted as part of manufacturing—such as logistics, warehousing, and transport—are increasingly outsourced to specialized service providers, and therefore no longer recorded under manufacturing output. As a result, services come to dominate GDP in advanced economies[i].

Figure (1): Manufacturing Share in GDP: The Inverted-U Pattern

While this pattern can also be observed in developing countries, a key concern is that it now tends to occur earlier and at much lower income levels than it did historically for advanced economies. This has led many developing countries to shift toward service-based economies without fully experiencing industrialization, a phenomenon known as premature deindustrialization. In this context, low-income economies begin to deindustrialize before manufacturing has generated its full potential in terms of productivity growth, employment absorption, and export capacity[i].

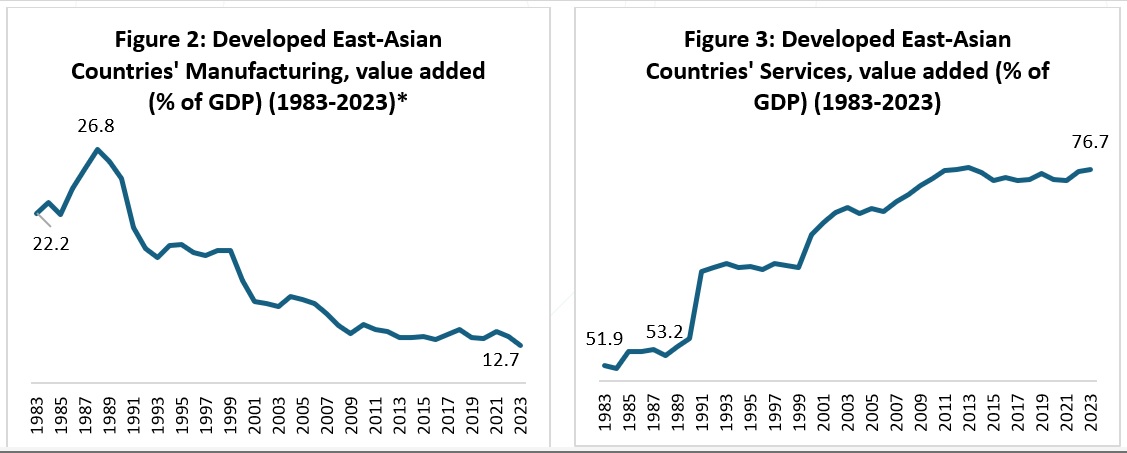

The experience of developed East Asian economies illustrates the intended sequence of structural transformation. Figure (2) shows the evolution of manufacturing value added as a share of GDP in developed East Asian countries between 1983 and 2023. Manufacturing accounted for an average of 22.2% of GDP in 1983, rising to a peak of 26.8% in 1988. By 2023, this share had declined to below 12.7%, reflecting a mature process of deindustrialization following decades of successful industrial growth.

In parallel, Figure (3) depicts the expansion of the services sector over the same period. Services contributed an average of 51.9% of GDP in 1983, increased modestly to 53.2% by 1988, and then rose steadily to reach 76.7% of GDP by 2023. This shift underscores that advanced economies did not abandon manufacturing prematurely; rather, they first achieved high income levels and strong industrial foundations, before transitioning toward services.

Source: World Bank

*Developed East-Asian Countries: Singapore, Hong Kong, Macao, South Korea, Japan [i]

Taken together, these patterns reinforce a central message: deindustrialization is not inherently problematic when it occurs after manufacturing has fulfilled its transformative role. The danger arises when countries move into services too early, before industrialization has delivered sustained productivity growth and broad-based employment.

This risk is particularly relevant for countries such as Egypt, where manufacturing has not yet reached its potential and its share of GDP is not increasing rapidly enough. Prematurely moving away from manufacturing could weaken the country’s industrial base and limit long-term growth highlights.

The Case of Egypt: Unlocking Upper Egypt Potential

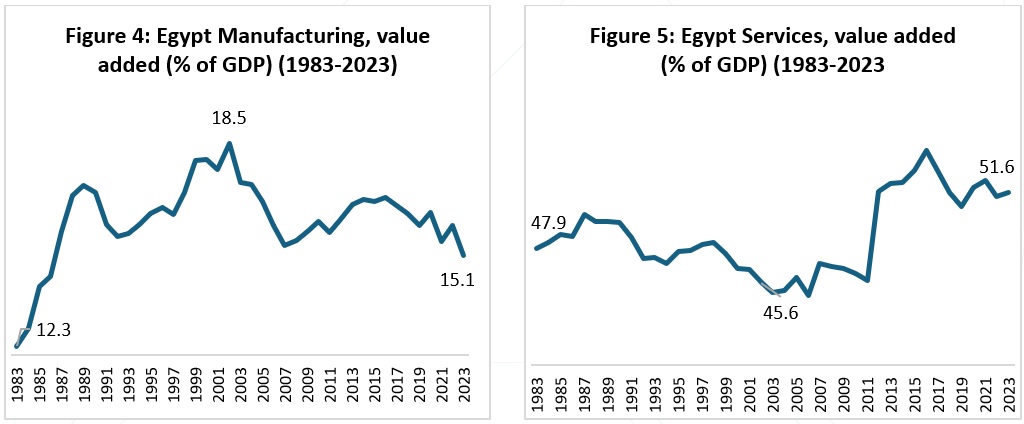

Egypt’s experience reflects many of the characteristics of premature deindustrialization, where the shift toward services occurs before manufacturing has fully delivered its developmental benefits.

Figure (4) illustrates the evolution of manufacturing value added as a share of GDP in Egypt between 1983 and 2023, while figure (5) traces the corresponding trend in the services sector over the same period. In 1983, manufacturing accounted for 12.3% of GDP, rising gradually to a peak of 18.5% in 2002. However, this upward trajectory was not sustained. By 2023, manufacturing’s share had declined to below 15.1% of GDP, indicating a reversal before reaching the levels typically observed in successful industrializers. In contrast, services represented 47.9% of GDP in 1983, declined slightly to 45.6% by 2002, and then expanded steadily, reaching 51.6% of GDP in 2023.

Crucially, Egypt’s peak in manufacturing did not coincide with the socioeconomic conditions usually associated with a mature industrial phase. In 2002, when manufacturing reached its highest share of GDP, poverty rates exceeded 17%, GDP per capita growth was only 0.3%, and unemployment stood at around 10% within a labor force of approximately 21 million.[i] [ii]These indicators suggest that manufacturing had not yet generated the broad-based income growth, employment absorption, or productivity gains seen in countries that successfully completed the industrialization phase.

Despite this, Egypt began to shift away from manufacturing and toward services before reaching high-income status, effectively deindustrializing prematurely. This transition occurred while the industrial base remained shallow and insufficiently upgraded, limiting the economy’s ability to sustain long-term growth. As a result, Egypt has remained a lower-middle-income country, with GDP per capita growth reaching only 0.6%[i] in 2024. Manufacturing accounted for just 13.9% of GDP, moving the economy further away from its 2030 target of raising the industrial sector’s contribution to 20% of GDP[ii].

Source: World Bank

Nevertheless, Egypt continues to possess substantial untapped industrial potential. The country holds competitive advantages in several manufacturing sectors, including food, beverages and tobacco products; textiles and apparel; leather products; chemical products; non-metallic mineral products; and basic metals[i]. Many of these industries are labor-intensive and rely on low- to medium-skilled workers, a resource that Egypt possesses in abundance—particularly in strategically important regions such as Upper Egypt. For instance, the textile industry, one of the most employment-intensive manufacturing sectors, offers a viable pathway for transitioning workers out of agriculture and into industrial employment, while simultaneously laying the foundation for future industrial upgrading.

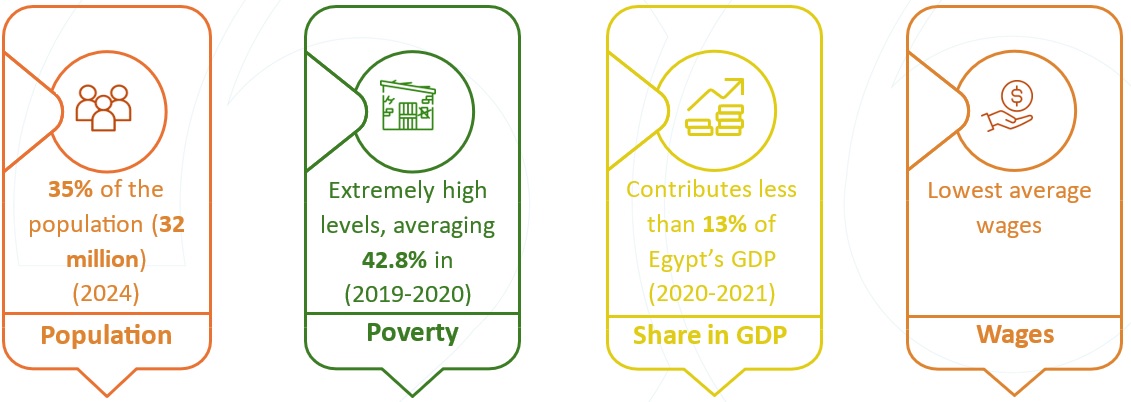

Within this context, Upper Egypt offers a strategic entry point for enhancing industrialization in Egypt. The region has substantial potential that remains largely untapped, particularly in sectors such as manufacturing and eco-friendly industries. Although it contains about 35% of the population, it contributes less than 13% of national GDP and remains one of the poorest and most underdeveloped regions in the country, with approximately 42.8% of its population living in poverty. [i] [ii]

This highlights the urgent need for sustainable development initiatives that can drive economic growth while enhancing industrial capacity and improving living standards. For instance, the establishment of an Eco-Industrial Parks Corridor Project in Upper Egypt can help transform one of the country’s underserved and least industrialized regions into a hub for sustainable, export-oriented manufacturing.

The initiative is built on a private-sector–led model in which industrial developers drive the development of eco-industrial parks in Upper Egypt through land allocation and phased, multi-use development. By facilitating domestic and foreign investment and integrating targeted skills and capacity-building programs for local communities, the project aims to expand industrial capacity, strengthen human capital, and enhance export competitiveness. Aligned with Egypt’s Vision 2030 and the SDGs, the corridor supports inclusive growth, poverty reduction, and the strategic objective of positioning Egypt as a regional hub for green industries while scaling value-added exports beyond USD 100 billion.

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

[1] Manufacturing-Led Export Strategies Still Make Sense

[iii] East Asian Miracle’ through industrial production and trade lenses

‘East Asian Miracle’ through industrial production and trade lenses | Industrial Analytics Platform

[iv] Manufacturing the future: The Next Era of global growth and innovation

mgi_ manufacturing_full report_nov 2012.pdf

[v] Premature deindustrialization

[vi] Higher Education Expansion and the Rise of the Skill-Intensive Sector

[vii] wp-non-tradeables-inclusive-growth.pdf

[viii] Premature deindustrialization

[ix] Premature deindustrialization

[x] mgi_ manufacturing_full report_nov 2012.pdf

[xi] Dani Rodrik, Premature Deindustrialization

[xii] World Bank country classifications by income level for 2024-2025

[xiii] Arab Republic of Egypt Poverty Reduction in Egypt Diagnosis and Strategy

[xiv] Poverty in Egypt during the 2000s

[xv] GDP per capita growth (annual %) – Egypt, Arab Rep. | Data

[xvi] Egypt to increase industrial sector contribution to GDP to 20-30%-SIS

[xvii] RCA Radar | UNCTAD Data Hub

No comment